A Transition to Occupation-Based Care Implementing AOTA’s Choosing Wisely® Recommendations in a Medical Model Rehabilitation Setting

AOTA’s Choosing Wisely recommendations encourages and empowers occupational therapy practitioners to get back to the roots and treat the person for their goals for health and well-being.

AOTA’s Choosing Wisely recommendations encourages and empowers occupational therapy practitioners to get back to the roots and treat the person for their goals for health and well-being.

By Kristin Hull, OT Practice publication on pages 21-24

When transitioning practice from an impairment-based focus to a client-centered, occupation-based focus, occupational therapy practitioners play an important role in encouraging client participation in collaborative goal setting for return to meaningful occupations. Within the medical model rehabilitation setting, there is dynamic involvement with the client, the staff, the demands of the workplace, and the environment.

Client participation differs across contexts, and even within physical medicine and rehabilitation, it is considered a diverse concept (Melin, 2018). Workplace demands can also add challenges, including competing responsibilities, productivity standards, and overall time constraints (Maitra & Erway, 2006; Skubik-Peplaski, 2012). With documentation technologically advancing, the electronic medical record system can limit practitioners' skill justification through the documentation system's structure (e.g., checkbox formatting or documentation flow within the system).

Resources may be insufficient, including therapeutic equipment access (Wong et al., 2018), not to mention a less natural environment that hinder skill carryover, such as a therapy gym equipped with non-purposeful, preparatory equipment (Skubik-Peplaski, 2012). To change practice and shift a culture of impairment-based treatment in a medical setting in a time of value-based reimbursement requires patience, support, and persistence.

This article describes the process and experiences of transitioning to occupation-based and client-centered care at the Rehabilitation Hospital of Indiana (RHI) using the American Occupational Therapy Association's (AOTA's) Choosing Wisely® recommendations.

Background

RHI is a rehabilitation network located in Indianapolis, Indiana, offering specialized and collaborative services along the care continuum for individuals 15 years of age and older through acute inpatient rehabilitation; three outpatient locations; and programs including community reintegration, research, and resource facilitation (for persons with brain injury and other neurological conditions across the state of Indiana).

Previously working as full-time clinical staff and now in dual roles as the Therapy Education Coordinator and supplemental occupational therapist, I understood the challenges of implementing client-centered care in a medical setting. I proposed an idea in 2018 to the Executive Director of Therapy Operations, Christina Baumgartner, to use my allotted continuing education funds to purchase items to construct functional, occupation-based kits to enhance client-centered outcomes. Baumgartner not only believed that this was a substantial opportunity to enhance care, but she also fully supported the materials financially.

Process

Initially, a peer group of inpatient occupational therapy practitioners created ideas for four occupation-based kits. They chose items based on the demographics of the client population across the hospital, client goals and needs, and discharge status to home.

The four kits were:

- Tool Kit: tool box, paint tray, rolling brush, paint brush, tape measure, level, flashlight with batteries, master lock, tool belt, hammer, Phillips screwdriver, flathead screwdriver, sander sheets, and lightbulbs

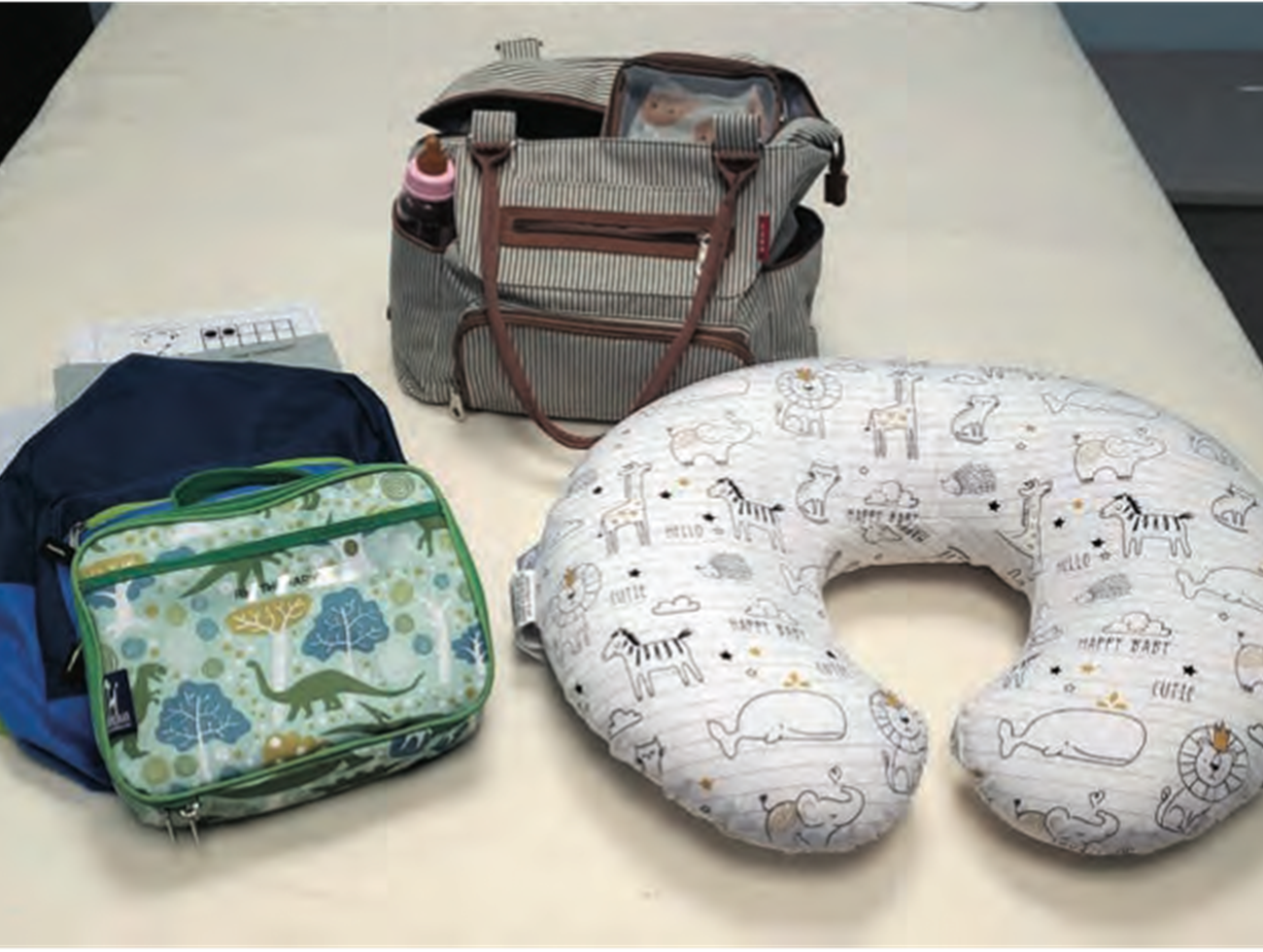

- Parenting Kit: diaper bag, wet wipe pack, zip pouches, diapers, changing mat, baby carrier, swaddles, play mat, pack n’ play, Boppy pillow with cover, backpack, lunch bag, binder, and folder with worksheets

- Home Care Kit: broom and dust- pan, spray bottle, vacuum, cleaning bucket, extendable duster, and Swiffer sweeper

- Travel Kit: suitcase, toiletry kit with grooming items, road atlas, wallet, tickets, hotel keys, shorts, shirts, underwear, and socks.

Parenting kit.

Parenting kit.

In conjunction with kit development, a transitional period began that emphasized evidence-based care throughout the network. A therapy in-service in June 2019 led by in-house researcher and physical therapist George Hornby, PT, PhD, highlighted the levels of evidence with application to client care to increase understanding and translation of evidence into practice.

Additional educational in-services continued to emphasize client-centered, evidence-based care, including a July 2019 in-service for all disciplines led by me and Stefani Soucy, OTR, CSRS, CBIS, titled “Patient-Centered Care in the Medical Setting: Thinking in a Different Light.”

That same month, during a meeting with the occupational therapy team and therapy leadership, AOTA’s Choosing Wisely recommendations were introduced and became the focus of occupational therapy practice through education and discussion. We provided details on the development of the recommendations per the article “AOTA’s Top 5 Choosing Wisely Recommendations” (Gillen et al., 2019), and introduced the four functional kits highlighting the use of purposeful activities through meaningful, relevant interventions (Recommendation #1), with physical agent modalities (Recommendation #3), and with cognitive-based training (Recommendation #5).

Open discussion among the occupational therapy team brought new ideas for item use and for additional items based upon RHI patient contexts. The inpatient and outpatient occupational therapy teams created a list of more than 150 items to meet patient needs, including but not limited to pet care, lawn care, and meal preparation. The RHI Executive Director of Therapy Operations supported all of these new items to enhance care, and Hull organized and coordinated items and developed an inventory list to assist practitioners.

To continue to supplement occupation-based interventions and support RHI’s occupational therapy practitioners, monthly Case Study Club meetings allowed the team to meet in smaller, organized sessions to discuss planned topics, including:

- Increasing our occupational therapy team’s familiarity with the functional inventory lists and the AOTA Choosing Wisely recommendations by working through clues during a functional breakout box activity.

- Creating an “Occupation-Based Tool Kit” for and by the RHI practitioners for a reference list to apply functional items from a top-down and bottom-up approach when in a pinch.

- Identifying program-based or client-based challenges with open discussion and collaborative problem solving to address psychosocial adjustment post-amputation and functional activities to achieve core and proximal strengthening post-transplantation.

- Reviewing assessment tools with a focus on client-centered and occupation-based goal setting to enhance understanding and application.

- Addressing physical agent modality use per AOTA Choosing Wisely recommendation #3, with evidence and discussion for occupation-based activity application during electrical stimulation.

In February 2020, RHI hosted its first occupational therapy continuing education workshop to continue to support inpatient and outpatient practice needs. Therapy leadership collaborated with Kim Waddell, PhD, OTR/L, to coordinate education and training for treatment selection and implementation, influenced by the principles of neuroplasticity. The workshop addressed task-specific training to highlight intensity, specificity, and repetition with functional application. This opportunity enhanced clinical reasoning and problem solving by demonstrating how to intensify functional, goal-centered activities.

Support

Throughout the process, RHI occupational therapy practitioners have been very fortunate to receive support from all levels of leadership, including financial, ethical, and professional growth. Therapy leadership, including therapy managers, the program director, and executive administrators, participated in meetings and in-services and have been available for discussion and collaboration.

Executive administration involvement has occurred in the monthly Case Study Clubs by our Chief Executive Officer and Chief of Medical Affairs to support our practitioners and evidence-based practice. Additionally, AOTA has provided support via email through discussion and collaboration, offering ideas for the challenges we faced. To create a significant, successful change requires support from oneself, peers, leadership, and professional organizations.

Challenges

With any significant change also comes challenges. Through this process at RHI, we have experienced challenges with process planning, active practitioner participation in meeting discussions, understanding how to apply evidence and translation to practice, and the impact of functional items on psychosocial needs. Although challenges may be discouraging, they also present as opportunities for process improvement to understand and identify areas of need, education, and support.

Preparatory Items Purged. During the meeting for the Choosing Wisely recommendations with the occupational therapy teams, I announced a plan to relocate preparatory items to the back of the gym with newer, functional items placed in easily accessible locations. In the following weeks, practitioners who were excited for the transition to new equipment assisted with cleaning cabinets. Instead of just relocating items, multiple preparatory items were purged without notifying the entire team. Unfortunately, the lack of communication about purging these items led to consternation among the occupational therapy department when the items could not be found for treatment sessions. The Executive Director of Therapy Operations held a meeting to openly discuss staff concerns, address communication, and create a plan to continue to support and pursue occupation-based transitions. Case Study Clubs also aimed for open discussion and to provide continued support and encouragement through communication.

Limited Participation. Initially, Case Study Club met in the open gym during lunch hour. Practitioners expressed needing this time to complete documentation to meet productivity standards, and conveyed frustration with these mandatory monthly meetings and the loss of clinical time. Case Study Club occurs two times per month, with monthly topics, to allow for smaller groups and to increase variety and view- points in discussion. The meeting space transitioned to a smaller conference room to allow a greater personal and personable atmosphere to encourage dialogue and discussion. RHI leadership presence in these meetings offered opportunities for discussion and to expand their understanding of the professions scope of practice and clinical reasoning surrounding the case studies, interventions, and current evidence. At each meeting, practitioners are provided with specific objectives and material based on the feedback received during and outside previous meetings.

Evidence. Implementing occupation-based services in a setting surrounded by condition-specific language and outcomes requires not only continued advocacy but also shifting an entire mindset while creating new habits and routines for practitioners, medical professionals, and clients. The transition from impairment-based language encourages identifying, understanding, and translating relevant research into practice. Challenges with evidence implementation experienced at RHI and the published literature include time, knowledge, resources, organizational culture, and interpersonal relationships (Warren et al., 2016).

Addressing Coping Needs. Practitioners often expressed concern over potential emotional setback for clients when using goal-centered objects or activities that a client would not be able to do as they had before impairment or injury. Before implementing the Choosing Wisely recommendations, practitioners had used preparatory items as an introductory task for clients in reaching and grasping to offset the psychosocial adjustment after impairment or injury. They transitioned to goal-centered activities when the practitioner or combined practitioner and client thought the client would be emotionally ready.

Activity analysis, therapeutic use of self, and client-centered care lie within the process of occupational therapy, and following the implementation of the recommendations, practitioners began to use purposeful activities and occupations instead of preparatory items. To use a client’s specific goals as the means and the end increases success and motivation for both the client and the practitioner.

Moving Forward

The process continues to be just that—a process. However, at RHI, we plan to keep moving forward and to continue to focus on the positivity. We look to enhance growth in knowledge of research and evidence implementation to improve skills and attitudes. Communication and transparency remain at the forefront of identifying challenges. Practitioners individualized interventions for the client, and each one brings unique ideas and knowledge. According to Myers and Lotz (2017), “The most promising training programs for increasing EBP appear to be those that include context-specific, collaborative approaches with multiple components and social learning opportunities” (p. 230). RHI will continue to explore and offer resources and opportunities for positive collaboration.

Metzler (2019) encouraged occupational therapy practitioners to “get out of the gym and into the patient’s roles, habits, and routines” (p. 8). Intervention planning comes from your client as AOTA’s Choosing Wisely recommendations encourage and empower us as occupational therapy practitioners to get back to our roots to treat the person for their goals for health and well-being. Embrace the process as a journey of change and look to those challenges as opportunities.

References

Gillen, G., Hunter, E. G., Lieberman, D., & Stutzbach, M. (2019). AOTA’s top 5 Choosing Wisely® recommendations. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73, 7302420010. https:// doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2019.732001

Maitra, K. K., & Erway, F. (2006). Perception

of client-centered practice in occupational therapists and their clients. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 60, 298–310. https://doi. org/10.5014/ajot.60.3.298

Melin, J. (2018). Patient participation in physical medicine and rehabilitation: A concept analysis. International Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation Journal, 3(1), 36–42. https://doi.org/10.15406/ ipmrj.2018.03.00071

Metzler, C. A. (2019). The future is now: How occupational therapy can thrive. OT Practice, 24(7), 8–9.

Myers, C. T., & Lotz, J. (2017). Practitioner training for use of evidence-based practice in occupa- tional therapy. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 31, 214–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/0738 0577.2017.1333183

Skubik-Peplaski, C. L. (2012). Environmental influ- ences on occupational therapy practice [Doctoral dissertation, University of Kentucky]. University of Kentucky’s UKnowledge. https://uknowledge. uky.edu/rehabsci_etds/23/

Warren, J. I., McLaughlin, M., Bardsley, J., Eich,

J., Esche, C. A., Kropkowski, L., & Risch, S. (2016). The strengths and challenges of imple- menting EBP in healthcare systems. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 13, 15–24.

Wong, C., Fagan, B., & Leland, N. E. (2018). Occupational therapy practitioners’ perspec- tives on occupation-based interventions for clients with hip fracture. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72, 7204205050. https:// doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2018.026492